When God Left The Pitch: What Made Maradona Football’s Deity

Do you know why my heart is beating? I saw Maradona. Hey mama, I’m in love. - Song from the stadiums

In Villa Fiorito a young boy wearing a number 10 jersey is asked what he wants from life. ‘I have two dreams’ he says, ‘the first is to play in the World Cup and the second is to win it.’

Diego Maradona’s life was as biblical as the first coming of Jesus, as stirring as the tale of the underdog who triumphs in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles. There is no number of words that can summarise someone who so transcended definition in football that they dubbed him first a king, then a God, then king of Gods.

Maradona grew up in the slums of Villa Fiorito, a town south of Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires. It was here that whilst scrounging around the dirt roads for scraps of tinfoil to sell that he discovered his innate talent for football. Gathering in the dangerous streets of the provinces with the other local kids he would engage in fast, dynamic games of street football – cumulative games where the scoreboard lay abandoned. A young Maradona would guide the ball over uneven terrain, potholes, patchy grass, boggy mud and through puddles. Almost as if it were written, he would display the same masterful control of the Earth’s elements over the notoriously uneven pitches in Latin America in the 80s and early 90s.

For so many children in Argentina even today, football remains the one true escape from a life of abject poverty, violence, drugs and homelessness. And for those of them who make it, it carries them out of the slums and onto a life of previously unimaginable prosperity.

Being Maradona has always come at a high price. Many players who had the privilege (or misfortune) of meeting Diego on the pitch quickly realised that there was no legitimate way to defend against him. His feet were too quick and his brain too hardwired to the pitch to catch him once he had possession. Throughout Maradona’s years on the field he was victim to countless eye-watering tackles, illegal kicks and dangerous ankle taps. You can’t stop what you can’t catch, so players resorted to inflicting injury in any way they could and more often than not referees inexplicably forgot they had a whistle. During his time at Barcelona in a match against Atletico Bilbao - a notoriously aggressive team - Maradona was stretchered off with a broken ankle after a horrendous tackle from behind by the “Butcher of Bilbao” Andoni Goikoetxea. During this Wild West period of football pre-1990s, the sport was not tempered by the rules that are in effect today. Players could brutalise each other on the field and get away with it.

Maradona came to face Bilbao again during his final game with Barcelona which signalled the end to a fraught two years at the club during which time he was outcast by locals who called him a ‘sudaca’ - an offensive term for a brown-skinned South American. Amidst the brewing animosity at the Copa Del Rey finals, a bruised and battered Maradona who had been chopped down constantly in savage attempts to stop him from playing finally snapped. After the final whistle sounded and Bilbao’s victory was sealed the winning team’s elation quickly turned hostile, substitute Miguel Sola sending a ‘fuck off’ hand gesture towards Maradona. The Argentinian, who was finished with restraining his anger lashed out at him with a knee to the face, knocking him out cold. His Barcelona team mates quickly joined in on what had instantly become gladiatorial entertainment for the crowd who surged forward in the stands. Flying kicks were sent studs-first into any red-and-white-shirted figures on the field. Officials, staff and paramedics flooded the pitch almost instantly as chaos erupted. Maradona came up against Goikoetxea again - the man who nearly ended his career, this time sustaining a kick to the thigh which left the impression of stud marks. The brawl in 1984 has to be seen to be believed. What was likely a lustral experience for Maradona and a tense one for both teams was a product of the overt racism against those of a similar background in Europe at the time. Maradona was banned for two months by the Spanish Football Association but never served his punishment as he left right after in search of calmer shores in Italy.

After leaving Barcelona, Maradona went to play for Napoli in the South of Italy. To this day Naples continues to be one of the poorest cities in Europe and Napoli the poorest football club in Italy. And so, the most expensive football player in history at that time became property of the Neapolitan people.

Naples was a rough city marred by mass unemployment, poverty, and organised crime. The prosperous, middle-class North dismissed the South as a stain on the nation. The Neapolitan people suffered greatly, but their passion for football endured. In this city of the slurred dialect where the people were downtrodden, the streets grimy and the coffee as potent as the drugs, Maradona recognised himself. Naples itself would come to be his exaltation and his crucifixion.

Since the 1980s, Naples had become a dumping ground for waste and later toxic waste when the mafia gained a lucrative monopoly over the garbage disposal system. When Maradona came to town, not only were the people poor, but they were sick as well. But in their football deity they saw a person just like themselves, who came from the same struggles and oppression, who gave meaning to life and gave pride to Napoli.

Football stadiums in Italy were hotspots for racism. Matches between Northern and Southern teams became orchestras of verbal abuse. ‘Disgusting peasants’ Northern teams would yell at Neapolitans during games, ‘Vesuvius, wash them with fire.’ The racism in Italy was palpable - something that was felt before it was heard. But now Napoli had Diego, and with him they were united against the loathed North. Maradona led Napoli to their historic, first ever win of the 1987 Italian championship. The final victory against the Tuscan team Fiorentina saw the city erupt into a two-month-long party. Amid the chaos of flares, music, and uncontrollable joy a banner was hung in front of the cemetery, a single sentence capturing the monumentality of this transcendent event, and an uncharacteristic pity for the dead; “You don’t know what you have missed.”

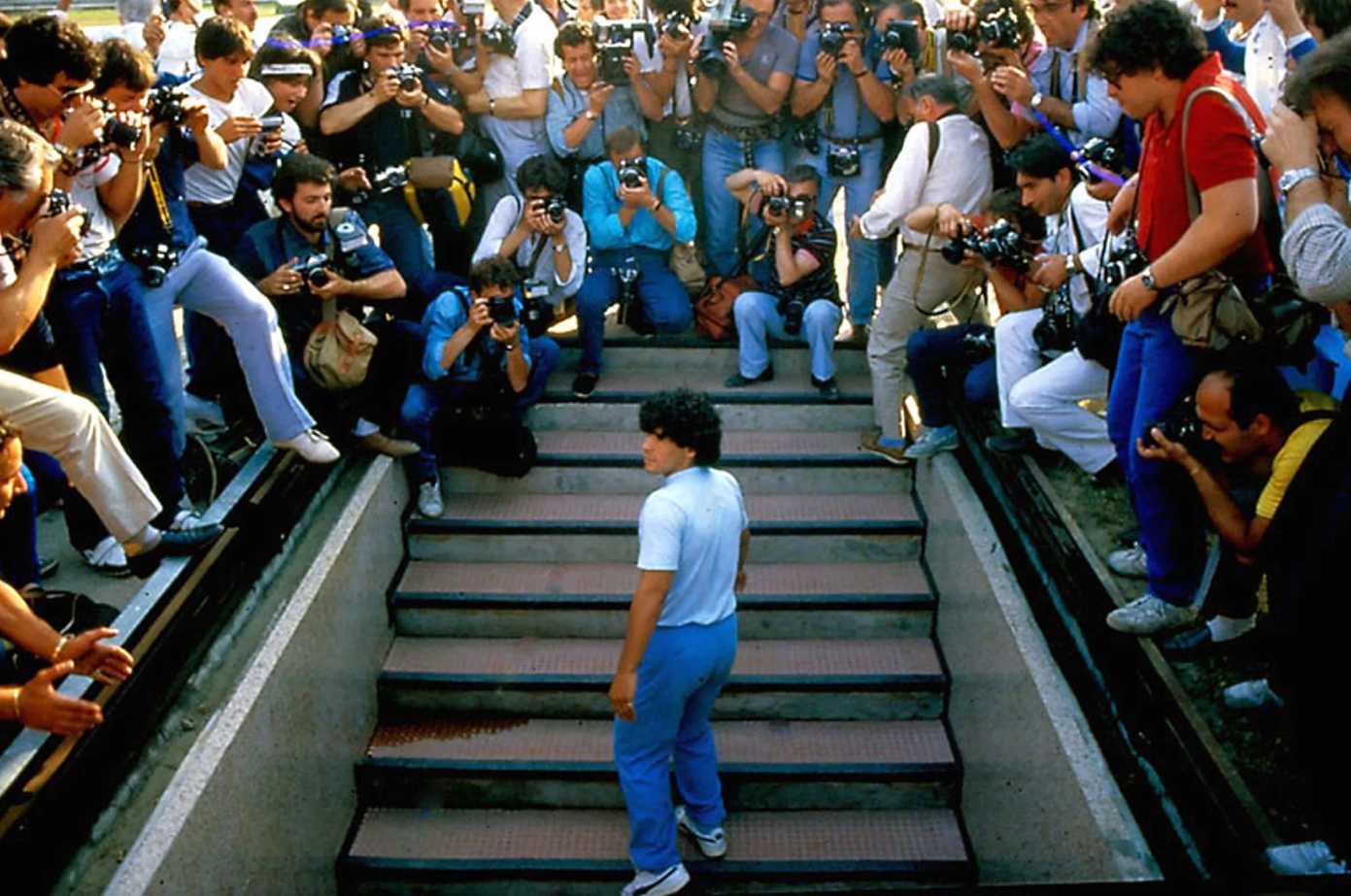

The people were enamoured, the streets became splashed with murals depicting Diego. Napoli’s patron saint Gennaro was replaced by the God of football in every street altar. The colours of Napoli, only a shade away from the sky blue of Argentina streaked the walls, the cars, and the people. Maradona’s disciples as well as the press followed his every move. There was nothing he could do without an enthusiastic audience who believed they were in the presence of God himself and were prepared to risk it all for a moment they could tell their grandchildren about.

It’s these stories that are being recounted today. Through God-given talent Diego Maradona rose up from his poverty-stricken youth and lifted up not only his family, but the people of Argentina, the people of Napoli, and captivated the rest of the world. He lifted entire nations and crafted whole identities for us to cling to, to cheer for and to weep for.

He carried all of our burdens - the intensity of a football match, or of 581 of them. The combined pain and glory of tournaments and press runs. The stifling discomfort of giving your identity over to fame. The agony of drug addiction, of loving and losing, of being human. And at the end, the unbearable weight of illness, of entrapment in the body. Faced with the invasiveness of fame Maradona abused drugs and then they abused him. He abused alcohol and then it returned the favour. But through various addictions; to drugs, to food, to football - he was always el pibe d’oro - the golden kid.

For Diego’s every step closer to immortality, his demise loomed nearer and nearer, and it would be at his own hand - the Hand of God - that his ascension would come. Diego Maradona is one of the few of us who go to heaven having lived vividly through every victory and every disaster, having confronted each one with his bullish intensity and his tender ardour. Having owned and made peace with each and every triumph and mistake.

Diego was always possessed by emotion. At the 1990 World Cup final in Italy, his anger was captured on camera as he yelled profanities during the Argentinian national anthem. Throughout the anthem Italian fans in the packed-out stadium whistled and jeered at the ‘traitor’ who had knocked Italy out of the competition after 7 years of winning glory for Napoli. During his time coaching Sinaloa Dorados in Mexico, he threw punches when provoked by a frenzied hoard of the opposition’s fans who chanted ‘Maradona eats it’ after his team lost a critical match. From sobbing on camera in victory and defeat, in glory and in pain, grief, and longing. He was never a stranger to a tango in the locker room or on live television, even recording a few songs - a tango, a ballad for his mother, a few cumbias.

How many people can you say felt everything and felt it deeply before their time was up?

Diego Maradona didn’t ever find boots that were big enough for him. He went from one team to the next, playing, managing and through it all battling personal demons, navigating complex family dynamics and living a life that was as full of adoration as it was malevolence. Maradona was as flawed as any of the ancient gods that humans have prayed to in times past, tortured by the media who made a pantomime of his life and a joke of his many struggles, spinning tragedy for tabloids. In life he was already a mystical figure - a human god, as alive and real as the next person. In death he represents a game that no longer exists. An era is over. As Lionel Messi payed tribute, ‘he has left us but is not gone, because Diego is eternal.’

During the quarter final against England in the 1986 World Cup, Maradona shot forward with the ball, evading English defenders and accidentally scoring with his hand as he jumped to head the ball. This goal made immediate history as the Hand of God, and another goal scored by Diego moments later as the Goal of the Century. At a time when the Falkland Islands/Islas Malvinas War was still fresh in Argentine memories and the colonial motives of England as rife as ever in Latin America, this victory was revenge served sweetly.

Britain may have popularised the sport, but Latin America gave it flair, gave it style and crafted its technicality. Until this moment England was held as football’s giant. In Mexico 1986, England found themselves within a saga of losses to Latin American teams - countries that were poor, that suffered decades of colonialist interference and imperialism, that were pitied and seen as easy to exploit. Maradona’s goals meant to the people of Latin America a rejuggling of the colonialist pattern at least on the football pitch. A squat, fiery, brown-skinned man with indigenous ancestry and built like a bull takes down an entire team of Englishmen. That’s Latin America.

What followed was decades of outrage by the English with many refusing to accept their defeat. In turn there has also been an English refusal to step back from imperialist meddling in Latin America.

Maradona’s matter-of-fact admission of the handball is the perfect summation of who he was. It was revenge, ‘like pick-pocketing the English’ he said. The Hand of God became a symbol of his life. The adversity and the hatred, the glory and the love, the media firestorm and the deification; In the end it was simply one of life’s many penalty shootouts; Sometimes the universe grants you a chance opportunity, sometimes not. Maradona was God because not only could he do things that nobody had ever seen, not only did he glorify Argentina and Napoli, but he also scored with a handball. Diego wasn't just the best at football - he transcended it entirely. And he didn’t only walk onto the pitch to play football, but to defend the people.

Maradona’s casket was displayed at Argentina’s government palace, Casa Rosada, the same place where he held the World Cup aloft in 1986 for thousands of cheering Argentinians. This time, Argentinians poured through the building for 11 hours weeping, tossing flowers and football jerseys at his coffin from behind the line of security guards, in the midst of the president’s declared three days of national mourning. From there, a motorcade accompanied the casket to the cemetery and was met by scenes identical to Maradona’s return to Napoli in 2005. Legions of fans clashed with police as they lined the streets, waved banners from the tops of cars and bridges and sang the songs of their idol one last time, catching one final glimpse of their God.

The spirit of Diego has always filled our house and our hearts. He was the closest link to my heritage in Argentina, Naples, and in football - a way to grasp something closer that at times has seemed so distant. Now he leaves us, ascending to a realm more suited to his otherworldly ability and larger-than-life personality. A place where he can play football forever more, never constrained by an earthly body again. Now when we look up, we know that Diego is there, probably still juggling that ball, still dancing through the pitch, still singing with the crowd.

He was one of those people who live closer to God than the rest of us, who only has to reach out a hand and feel the ethereal glow returned. In the end that was what he did. Countless times on the pitch and one last time at the moment of his death.

La pelota no se mancha - the ball doesn’t stain - but it turns to gold when el pibe d’oro touches it.